Titanic Struggle With Mesothelioma

Born in the ancient city of Athens, Greece in 1933, during the height of the Great Depression, Kerry Stamas survived. Hundreds of thousands of Greek civilians died during World War II. Only seven years old when Mussolini's Fascist Army invaded, Kerry's parents kept him safe by spiriting him away to a remote village in the hills. Fate spared him from earthquakes; a cataclysmic quake claimed his sister. Fortune smiled on him in so many ways -- classic good looks, uncommon physical strength at five feet, eight inches tall and 185 pounds. He honed his intelligence with a college education; he preserved his excellent constitution with exercise and a devotion to fitness and healthy eating.

Luck turned on Kerry. Uncaring men he would never meet placed an unforgiving monster in his chest -- in Iowa, of all places.

Kerry came there in 1955 after meeting his future wife Mary, an American, on a cruise ship. They married and settled down in Waterloo, where they raised two sons, George and Dean, and a daughter, Lisa. Kerry had earned a degree in electrical engineering in Athens, but had difficulty finding work as an engineer in America because his English was poor. He took a job as an electrician at a John Deere plant in Waterloo, and after about a year went to work for Iowa Public Service (IPS) at the Maynard Powerhouse in Waterloo. He perfected his English, but he remained at IPS as an insulator and certified welder, until his promotion to plant foreman in the late 1980s.

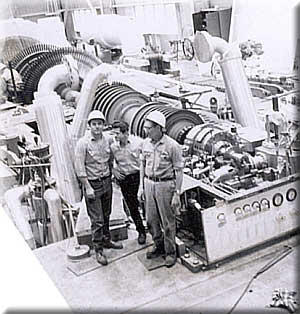

Kerry worked for close to two decades in air so contaminated with asbestos that at the end of the day he looked as if he had been rolled in greyish-white flour. He insulated high-temperature steam lines and other pipes. He used both sheet gasketing and preformed gaskets. He was heavily exposed to asbestos during boiler and turbine work. He performed regular maintenance on the turbines, which included tear-out and replacement of asbestos-containing insulation. He personally used insulating cement and at times raw asbestos in these jobs. He re-packed pumps. He used asbestos gloves when doing boiler work.

Three years before he retired in 1995, Mary passed away from a rare illness which should have taken her ten years earlier. He loved spending time with his grandchildren, but they were getting older and he was weary of Iowa's harsh winters, so he moved to the Gulf Coast of Florida. A chest film with a routine physical taken in 1996 showed that Kerry had bilateral calcified pleural plaques, or scarring on the lining of the lungs, a condition consistent with his heavy asbestos exposure. From that point forward, Kerry submitted to chest films every three months.

There was seemingly nothing to worry about. He was strong as a bull. He walked five miles a day and golfed once a week. Fate smiled again and matched him with another Greek-American, a very nice woman named Maria.

Around September, 2001, Kerry developed pain in the left side of his body. He consulted with his primary physician in Clearwater, Florida. His doctor felt he might have a pinched nerve in his neck. The pain did not subside, and the true nature of the problem continued to elude Kerry's doctor until May, 2002, when chest films revealed the presence of fluid in the left thoracic cavity.

Kerry was referred to a Clearwater cardiopulmonary specialist. On June 10, at Morton Hospital in Clearwater, a thoracic surgeon performed a thoracotomy with thoracoscopy, pleural biopsy, thoracentesis, and talc pleurodesis on the left side. The surgeon would not tell Mr. Stamas "anything" until the pathology laboratory at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, D.C. confirmed the diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma, desmoplastic (sarcomatous) type. Kerry was discharged from the hospital around June 16.

His late wife Mary had treated her illness with some success at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, so he decided to get a second opinion there. Mayo confirmed the diagnosis on July 3. Because sarcomatous mesothelioma is so aggressive, spreading so much faster than the epithelial type, the doctors at Mayo recommended neither surgery nor chemotherapy.

Working from her home computer, Kerry's daughter Lisa began scouring the Internet for open clinical trials which would take her father. She found none. For his part, Kerry set his will stubbornly, almost fanatically, on testifying at his deposition and then returning to Greece to see family in September. On August 29, 2002, his testimony stretched from 10 a.m. until 7 p.m. Kerry was the essence of dignified stoicism. He appeared trim, tan, silver-haired and handsome. He would have appeared to be in perfect health were it not for the grimaces of pain which flashed across his face. His pain grew noticeably as the day ground on mercilessly. At the end of the day, many of the defense attorneys belatedly murmured their sympathies, some clearly troubled by their line of work.

In the first week of September, Kerry traveled to Houston, Texas to seek experimental treatment at the Burszynski Clinic. His health was deteriorating. He now had pain on the right side as well as the left. He gasped audibly for breath. He said, "The last deposition really knocked me back; I haven't been the same since." Determined to go home to Greece one last time, but fully realizing he would never make it in his current state, he clung doggedly to the hope offered by Burszynski.

By the third week of October, CT scans show that his tumor has doubled in size. He was suffering severe shortness of breath, severe fatigue, poor appetite, night sweats and increasingly severe pain. On November 1, 2002, he presented to the Emergency Room of Morton Plant Hospital in Clearwater. Constipation associated with his pain medication had caused an abscess in his rectum. Corrective surgery was delayed until November 3 as he was on the blood thinning agent Cumadin and needed time to abstain from taking the drug preoperatively. He did undergo surgery for the abscess on November 3 and remained hospitalized for approximately eight days.

Blood work in December indicated that the tumor may have moved into the abdominal cavity. He was taking morphine, 30 milligrams, taken twice a day, and Vicodin, two 15 milligram tablets, taken every four to six hours for breakthrough pain as needed. His legs and ankles were noticeably swollen. He had clearly lost weight, but because of the large buildup of fluid in his legs and ankles it was difficult to determine precisely how much weight he has lost. He weighed 173 pounds, down from his normal weight of approximately 185 pounds.

Kerry's doctor recommended hospice care. A December 30 FDG-PET scan showed extensive pleural cancer in the left chest, probable diffuse pericardial metastasis with some direct extension into the mediastinum, and metastatic involvement of the sternum, left humerus, and right femur, with possible metastatic extension into multiple mid-thoracic vertabrae. But he fought on. As late as January 22, 2003, he was consulting with doctors to start new treatment to extend his life. But the next day found him in the hospital again, this time for four days. Lisa came to Kerry's side, to spend his last days with him. He passed away in the night on February 6.

When I first met Kerry, he told me how proud he was to be Greek and American. He told me that Greece was one of only three nations in the world beyond the former British Empire which allied itself with the United States in every major international conflict over the last 100 years. He told me that the city-state of Athens, his hometown, was the birthplace of democracy.

Kerry said that despite the cruel end he faced, he had enjoyed his life, and was comforted that our system of justice would compensate his family for his wrongful death. He heroically fought his pain, trying desperately to live long enough to step before a jury of his peers and tell the truth of what had been done to him. His case settled after his death, but he would have taken comfort in the measure of his life.

His daughter Lisa now worries over the impact of the pending Federal asbestos legislation, Sen. Orrin Hatch's "Fairness in Asbestos Injury Resolution" Act , not only upon the measure of justice given her father, but equally upon those still waiting for justice. She wonders whether the defendants who admitted their guilt for her father's death will walk scot-free. She thinks of her father's love for democracy, for this country, for our right to a jury trial, a right so sacred that her father held on to life heroically, long past the time when he could have realized any benefit for himself. She asks her Senators and Congressmen from Iowa, all of her countrymen, to remember that individual, fundamental human rights should not be sacrificed to the interests of large, inhuman corporations. She urges her democratically elected representatives to remember her father and defeat the Hatch Bill. She also expressed the following:

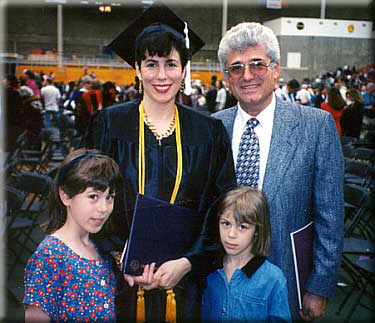

Dad was so proud of my college degrees and accomplishments. We dressed both of my daughters up in my cap and gown and took pictures. However, when my father first understood the implications of his disease, the first thing he said was "You mean I might not see my pumpkin graduate?" He said this with tears in his eyes and that was the only time I saw my father cry. He died before Sara graduated high school. His granddaughters were everything to him. He might not have been at Sara's graduation ceremony, but he was in our thoughts and heart.

I would like to address a message to the manufactures who made the asbestos that killed my father. The last few months of my father's life was pure hell but still he was determined to live. All he wanted was a few more years to spend with his family. His spirit was unbreakable. I was so proud of his fighting strength. But I am also left with the horrible images of what this disease did to him. You see, my father was a very strong man and capable man. I always knew that if something terrible ever happened to me that my father would be there for me. But at the end, Maria and I took care of him. He was too weak to walk unassisted or feed himself. He had to breathe with oxygen. His body had failed him. And in the end, when we put him in bed for the last time, I remember him reaching his arms out to me to take him out of there. He knew he was not going to get out of bed again. Whenever I think of my dad, this is what I see. So I have to put thoughts of him away for a while or only think of him for short periods of time because it hurts so much. A few months after he died I had a dream of my parents and that they were very happy together again. I have to believe that his suffering is over, at least for him. Mesothelioma should not have happened to my father nor to any of the other victims. The asbestos manufactures stole my father's life away and took him away from his family.

Kerry Stamas